Who Will Stand Against Reckless Banking?

Reviving the New Deal spirit might be the key to a stable banking system

First Republic Bank has become the latest financial institution to fail in recent months. JPMorgan successfully took over the bank and its $92 billion in deposits. While rising interest rates have brought on three of the largest bank failures in U.S. history since March, no one is predicting a rerun of the 2008 financial crisis. Nevertheless, it has cost the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) billions of dollars and prompted questions around how prepared the United States is for the next crash.

The Dodd-Frank Act, passed under the Obama administration and partially repealed during the Trump administration, remains the legal framework for financial regulation. Most would agree that the financial system is more resilient as a result, but the legislation was drafted to address the causes of the last crisis. We do not know where the next crisis might come from. It might not be the recent run of bank failures, but the risks posed by ‘too big to fail’ banks is still too high. This has not fundamentally changed since the Great Recession.

Arguably, no administration has made a serious attempt to curtail the power of finance since Franklin D. Roosevelt. The New Deal banking reforms provided stability for generations as well as saving the United States from the brink of collapse in 1933.

For much of nineteenth and early twentieth century American history, bank panics were a regular occurrence even after the Federal Reserve was founded. Between 1930 and 1932, there were 5,000 bank closures. Another 4,000 banks closed between January and March 1933. Roosevelt declared a four-day federal ‘bank holiday’ and Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act. In his first ever fireside chat, Roosevelt used a radio broadcast to explain his actions to an audience of 40 million Americans and to restore confidence.

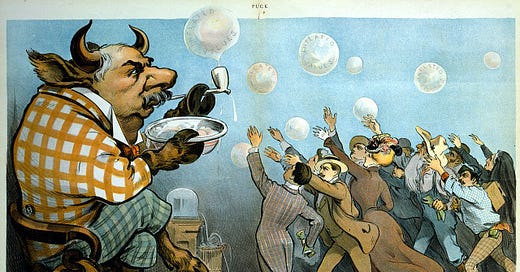

This decisive response saved the banks and was a formative experience for Roosevelt’s New Deal. To improve the long-term security and practices of the financial system, Roosevelt backed the Glass-Steagall Act. Jack Morgan, son of J.P. Morgan, called Roosevelt the “crazy man in charge” for his regulatory push. Roosevelt realized that his task was not just to reassure Americans that their deposits would be safe, but to also convince them that banks would behave responsibly and be held accountable for their actions. It went right to the heart of the Neal Deal’s promise that the government would deliver economic liberty, helping the ‘forgotten American’ against the abuse of power by big business.

Making his case for a second term, Roosevelt used a speech at Madison Square Garden on October 31, 1936, to declare:

“We had to struggle with the old enemies of peace--business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering.

“They had begun to consider the Government of the United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs. We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob.

“Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me--and I welcome their hatred.”

The present situation is a direct consequence of economic liberalization since the 1980s. Federal regulators were undermining the Glass-Steagall Act long before its repeal in 1999. Financialization of the U.S. economy has gone hand-in-glove with the off-shoring of manufacturing and the lowering of tariffs. To be serious about rebuilding the nation’s industrial base and expanding the middle class, the United States needs to overhaul the financial system alongside the revival of industrial policy.

The provisions in the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 that ringfenced investment and commercial banking have still not been reinstated. We can never know how effective this legislation would have been in mitigating the causes of the 2008 financial crisis, but it certainly kept the financial system secure while it was in place. Market concentration has only grown over the past decade in the absence of government action. This year’s bank failures have turbo-charged JPMorgan’s share of the banking sector, consolidating its position as the nation’s largest bank.

Pressure to follow Roosevelt’s example has come from progressives such as Senator Elizabeth Warren. Her proposed 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act would make a welcome start toward restoring the ringfencing of investment and commercial banking. Senator Josh Hawley has echoed these concerns. Even Donald Trump briefly considered supporting such a move in 2017. Joe Biden voted for repeal of Glass-Steagall in the U.S. Senate, a vote he later claimed to regret, but there is no sign of the Democratic leadership considering such a move.

Reforming the financial system might not carry the same level of urgency as the post-2008 period, but it remains vital to the future of American capitalism. Anger and distrust of Wall Street has continued to fester, contributing toward populist anger. Making sure Main Street gets a fair deal means getting Wall Street to work for the benefit of the nation. Whichever party takes the lead will reap a significant reward from the electorate and help the United States to build a more resilient economy.

This article is part of the American System series edited by David A. Cowan and supported by the Common Good Economics Grant Program. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors.

David A. Cowan is a Ph.D. Candidate in history at the University of Cambridge and a former staffer and researcher in the UK Parliament. He has been previously published at American Affairs, Engelsberg Ideas, and National Review.