What does the American System Mean Today?

The practical steps we should take to modernize Hamiltonian economics

by David P. Goldman

The principles that Alexander Hamilton enunciated in his Report on Manufactures and Report on the Public Debt still apply today, but policy implementation requires some updating to the economic circumstances of the 21st century.

Tariffs are a useful, indeed necessary, part of the policy mix, but the enthusiasm for tariffs today recalls H. L. Mencken’s quip, “For every complex problem there is a solution that is simple, clear, and wrong”. The United States has a chronic trade deficit in goods, now running at an annual rate of nearly $1 trillion a year. It also has a negative net foreign asset position of about $18 trillion, the result of thirty years of cumulative deficits. Its manufacturing industry is so depleted that it found itself unable to manufacture a sufficient supply of 155-millimeter artillery shells to Ukraine and Israel during the ongoing conflicts. The United States is also dependent on China, whose benevolence cannot be taken for granted, for a wide variety of critical products, ranging from pharmaceuticals to electrical switching gear. That is a problem, and a complex one. But are tariffs the solution?

The Limits of Tariffs

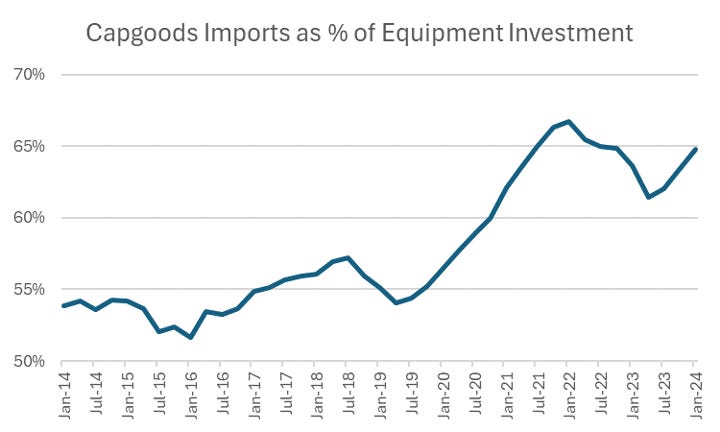

Some tariffs surely are part of the solution. But the United States is like a drug addict whose system is so depleted that cold turkey withdrawal would be fatal. Imports of capital goods are now equal to about two-thirds of nonresidential private equipment investment as reported on the GDP tables. The table below shows capital goods (excluding automotive) as a percentage of nonresidential private equipment investment. Because the latter figure includes some automotive investment (e.g., company car fleets), the actual proportion probably is higher.

Capital goods, of course, are goods used to produce other goods. To reduce the United States’ addiction to imports, we must produce more, which means we must invest in more capital goods. Our capacity to produce capital goods, though, is so diminished that we first would have to import more capital goods in order to be able to produce more, and thus import less in the future. We lack industrial capacity, infrastructure, skilled workers and engineers. Manufacturing is not a black box with a switch on the outside. It is an eco-system and a culture, that involves communities who provide skilled workers, educational institutions that train them, companies that hire managers who know their way around a factory, and governments that build the required infrastructure. Our eco-system has atrophied and our manufacturing culture has deteriorated. To restore it will require a set of remedies. This may seem complex, and it certainly would be expensive. But that’s the reality of the matter.

Tariffs raise the price of imported goods, giving domestic manufacturers an advantage. In some cases, they are indispensable. The United States has imposed a 27.5% tariff on imports of cars from China, which is now increasing to 102.5%. Without this, China would crush America’s auto industry. Whether this is due to Beijing’s subsidies to automakers or due to enormous economies of scale in the highly automated plants of the world’s largest producer is beside the point. No American manufacturer can compete with the $9,000 sticker price of BYD’s Seagull subcompact. The United States cannot afford to lose its auto industry, and there is a strong case for protection.

In other cases, tariffs may be harmful. To correct the trade deficit, we have to produce more at home, and to produce more we first have to invest more. For the first time in our history, though, we import more capital goods—the goods that make other goods—than we produce at home.

American industry depends on foreign components—especially Chinese components—for thousands of items that we no longer produce at home, starting with circuit boards, but including capacitors, switches, and a myriad of electronic parts. That is true even in the defense industry. Reported in the Financial Times on June 19, 2023:

Greg Hayes, chief executive of Raytheon, said the company had "several thousand suppliers in China and decoupling . . . is impossible". "We can de-risk but not decouple," Hayes told the Financial Times in an interview, adding that he believed this to be the case "for everybody". "Think about the $500bn of trade that goes from China to the US every year. More than 95 percent of rare earth materials or metals come from, or are processed in, China. There is no alternative," said Hayes. "If we had to pull out of China, it would take us many many years to re-establish that capability either domestically or in other friendly countries."

Selective tariffs, for example on Chinese EVs, are a crutch that our auto industry cannot do without. But an across-the-board tariff will raise the cost of capital goods. Among other things, it is a tax on capital investment. Our biggest problem is the reluctance of Americans to invest in capital-intensive industries. After the 2000-2001 recession, the smart money figured out that we could produce expensive software and let Asia make the hardware—first Japan, then South Korea and Taiwan, and then China. The marginal cost of selling a download of a computer program from a website is zero; not so the marginal cost of fabricating another computer chip or building a plasma screen.

Declining Capital Stock

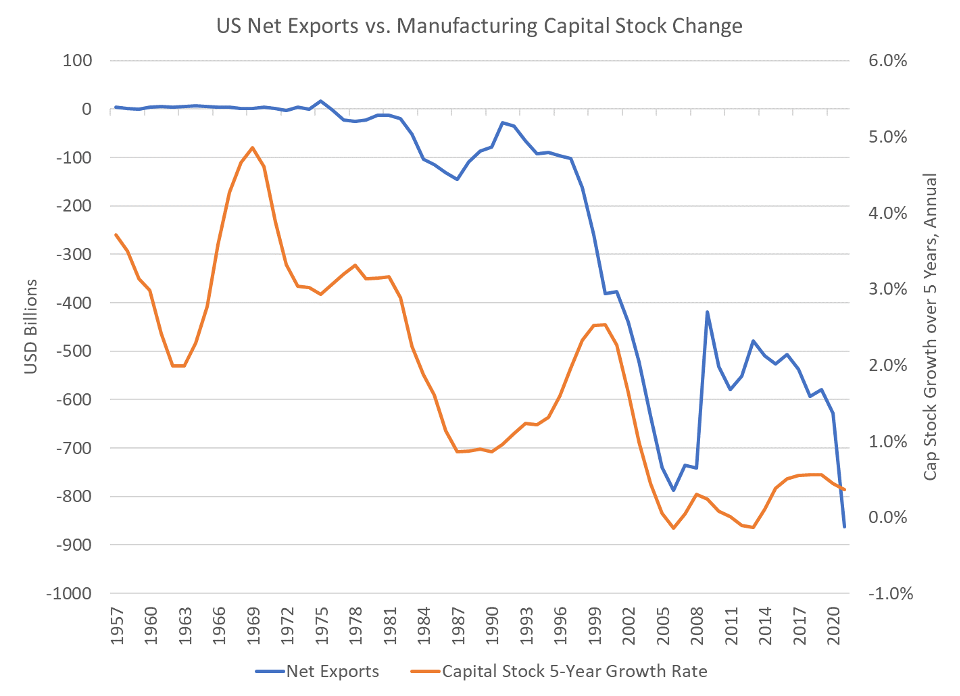

Our capital stock of manufacturing equipment stopped growing in 2001, according to Federal Reserve estimates. To get back to our long-term trend growth in manufacturing capital stock, US manufacturers would have to spend about $1 trillion for new equipment, nearly five years' worth of purchases at current rates.

There’s a clear correspondence between our trade deficit and the slowing growth rate of manufacturing capital stock. The growth rate of capital stock slowed well before the trade deficit ballooned during the 2000s.

Industrial production and employment in January 2024 were lower than in January 2007, just before the Great Financial Crisis. Manufacturing pay in constant dollars has not risen since 2009. Our stock of manufacturing capital equipment has not grown in 20 years. Even at depressed levels of employment, manufacturers cannot find skilled workers. The trade deficit remains close to $1 trillion a year, and the United States’ net foreign asset position, now at negative $18 trillion, continues to drift further into negative numbers.

Robert Lighthizer, Donald Trump’s Special Trade Representative, wrote in his book No Trade is Free: “Stable manufacturing jobs are a primary way for people without college degrees to comfortably support themselves, while enjoying the sense of dignity and pride that comes from making things.” That is how it used to be, and how it should be – but it is not that way now.

The average hourly manufacturing wage after adjustment for the Consumer Price Index has not grown since 2009. When real hourly manufacturing wages fell by nearly 10% between 2021 and 2023 due to inflation, manufacturing job openings reached the unprecedented one-million mark, before coming down to a still-elevated 600,000 as real wages improved.

The skilled labor shortage, to be sure, is not the only obstacle to US manufacturing. Excessive regulation and a tax code that favors “capital light” industries, e.g. software, at the expense of capital-intensive industries present stumbling blocks to manufacturing investment. The United States has an industrial policy that actively discourages industry.

It is a vicious cycle. Companies do not invest enough in new equipment, productivity stagnates, wages decline, and workers will not take low-paid manufacturing jobs. The National Association of Manufacturers worries that the United States will be unable to fill 2.1 million manufacturing jobs by 2030.

But manufacturers have not invested in new equipment. The rate of growth in the US capital stock of manufacturing equipment, according to the Federal Reserve, fell to nearly zero after the 2008 crisis and has not recovered. Real wage growth in manufacturing parallels the change in the capital stock, just as the textbook tells us: More investment means more productivity and higher wages, and vice-versa.

Dependency on China

Another challenge is that the Trump tariffs have not kept Chinese goods out of the United States. China's exports to the US surged to a post-COVID seasonally-adjusted peak of $52 billion a month in March 2022 from $38 billion in August 2019, when the tariffs were announced. China exported a seasonally adjusted $36 billion to the US in October 2023, according to US customs data. Chinese data show an increase from $34 billion in August 2019 to $42 billion in October 2023. The Chinese data probably are more accurate, according to a Federal Reserve study, because they include exports routed via third countries. More to the point, America’s trade deficit in goods and services was $48 billion in August 2019 (or $576 billion annualized). In October 2023 it rose to $64 billion, or $768 billion annualized.

According to recent studies by IMF economists, the World Bank, the Peterson Institute, Bank for International Settlements researchers, and others, tariffs have not made the US less dependent on Chinese supply chains. The Chinese shipped semi-finished goods and components to third countries for final assembly and re-export to the United States. As the BIS wrote:

"Firms from other jurisdictions have interposed themselves in the supply chains from China to the United States. The identity of the firms that have interposed themselves in this way can be gleaned from the fact that firms from the Asia-Pacific region account for a greater portion of suppliers to US customers than in December 2021, as well as accounting for a greater portion of the customers of Chinese suppliers.”

The World Bank economists put it this way:

“US imports from China are being replaced with imports from large developing countries with revealed comparative advantage in a product. Countries replacing China tend to be deeply integrated into China’s supply chains and are experiencing faster import growth from China, especially in strategic industries. Put differently, to displace China on the export side, countries must embrace China’s supply chains.”

The chart below sums up what has happened since the Trump tariffs on China went into effect in 2019. China’s exports to the Global South doubled from about $85 billion a month to $170 billion a month, while US imports from the Global South rose from $45 billion a month to $70 billion a month.

The United States imported less from China only because it imported more from countries dependent on Chinese semi-finished goods, components, and capital goods.

The Biden administration has done nothing to counteract these perverse effects. However, to its credit, the administration did adopt an industrial policy for semiconductors, namely the CHIPS Act. The main motive for the CHIPS Act is national security rather than economic efficiency. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s largest chip foundry and the largest single investor within the CHIPS Act framework, has said that the chips it produces in the United States will cost considerably more than the chips it sells from its foundries in Taiwan.

The Manufacturing Skills Gap

The stumbles and fumbles associated with the CHIPS Act should be an object lesson. TSMC will not open the first of two promised plants in Arizona until 2025, and delayed the second until 2026 and 2027, citing shortages of skilled labor. Samsung plans a Fab in Texas but delayed its opening by at least a year and is now considering delaying the project indefinitely.

The CHIPS Act started a construction boom, but the United States lacked the infrastructure and skilled labor to meet the subsidy-stoked demand. An all-time record 450,000 construction jobs were unfilled as of January 2024. The jump in construction job openings since 2020 coincided with an unprecedented 40% increase in the cost of new industrial building construction.

The United States also has a shortage of engineers. The biggest problem at US engineering schools—excluding a few top-rated schools—is finding students qualified to major in the subject at the undergraduate level. A key indicator of student demand for engineering programs at highly rated state universities is the engineering school acceptance rate. For many of the best state universities, the acceptance rate is 50% or higher, indicating an absence of demand for the major. Only 6% of American undergraduates major in engineering, compared to 33% in China and Russia.

In 1957, the National Defense Education Act responded to Russia's leadership in the space race after the launch of Sputnik, offering low-cost student loans and subsidies for university instruction in mathematics, science, and foreign languages. As a result, the number of engineering bachelor's degrees soared from 143,000 in 1955 to a peak of 350,000 in 1985, before falling in the 1990s.

The dumbing-down and diversification of American education undermines manufacturing. A commercial firm that recruits manufacturing workers advises prospective applicants that they require proficiency in decimals and fractions, coordinate geometry, and trigonometry. In 2009, 34% of US 8th graders tested at “proficient” (26%) or “advanced” (8%) on the National Assessment of Education Progress test. By 2020 that had fallen to just 24%, with 20% at “proficient” and 4% at “advanced, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. The 24% who are proficient in mathematics almost certainly will go on to university rather than apply for manufacturing jobs. Public policy that undermines mathematics and science at all levels of education requires correction by public policy.

For that matter, only 1.4% of American undergraduates major in mathematics. In 2021 the United States awarded just 30,202 degrees in mathematics. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that 33,500 mathematics-related jobs will open per month. Presently there are 1,413,345 math teachers in the United States, most of whom are trained in “mathematics education,” not mathematics. Most European countries require the equivalent of a bachelor's degree in mathematics as a prerequisite for teaching the subject in secondary school. At present graduation rates, requiring math teachers to earn a mathematics degree would take 47 years, provided that mathematics graduates did nothing but teach secondary school.

Renewing the American System

What will it take to persuade US manufacturers to invest in expensive, capital-intensive manufacturing? There are several issues, including:

Tax policy: Manufacturers must write off, or depreciate, their capital investments over a period of years. Inflation reduces the value of depreciation allowances.

Environmental regulation: Excessive regulation by the Environmental Protection Agency is an important obstacle to investment. The National Association of Manufacturers claims that 65% of its members would invest more with regulatory relief.

Infrastructure: Deteriorating US infrastructure is a major obstacle to large capital-intensive facilities.

Skilled labor: America still has 600,000 job openings for manufacturing workers, down from a million in 2022, but still exceptionally high. The National Association of Manufacturers warns that they will be short 3 million workers during the present decade. A European-style apprenticeship system with private-public partnerships would help train Americans for skilled jobs.

Federal support for technology: Federal R&D spending was 1.2% of GDP in 1983, when President Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative, but only 0.7% today. The great national laboratories at companies like Bell, GE, and RCA which produced so many of America’s signature innovations have disappeared along with federal funding.

Tariffs have a role to play in reviving manufacturing, but that role should be narrowly defined and industry-specific. Renewing the American System requires a comprehensive industrial policy. There is no way to climb out of the hole we have dug for ourselves without spending money – on tax relief for manufacturing investment, on infrastructure, and in rare cases such as semiconductors, on subsidies.

This article is part of the American System series edited by David A. Cowan and supported by the Common Good Economics Grant Program. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors.

David P. Goldman is deputy editor of Asia Times and a fellow of the Claremont Institute’s Center for the American Way of Life.

The urgent need to move to electric transport and scrap fossil-fuel transport means the world has to embrace Chinese EV production at the expense of employment in their own countries. It is better to pay people to do nothing than to do harm.