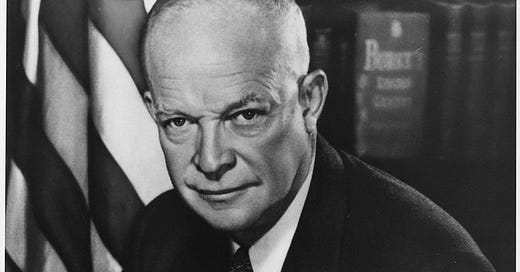

The Effective Conservative Governance of Eisenhower

The conservative successes of the Eisenhower administration have been too quickly forgotten.

by Geoffrey Kabaservice

This article first appeared on The American Conservative, October 15, 2022

President Dwight Eisenhower was the most fiscally conservative president of the past ninety years, yet he also expanded the scope and power of the state to fight and win the Cold War. Among the most successful of Eisenhower’s new institutions was what is now known as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA.

No Republican president since has come close to Eisenhower’s record of balancing the budget three times in eight years, cutting the federal workforce by more than 10 percent, slimming federal expenditures from 21 percent of GNP to 15 percent in his last budget, and reducing the ratio of national debt to GNP. At the same time, his global strategy of containing communism entailed major investments in education and research, huge infrastructural projects such as the national highway program, and the creation of new government agencies, departments, and other bodies.

Eisenhower created the Advanced Research Projects Agency (or ARPA, as it was then known) in 1958 as part of the national response to the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik I, the world’s first artificial satellite, the previous year. The Soviets’ surprise breakthrough suggested both that America’s Cold War nemesis was more technologically advanced than the United States, at least in the Space Race, and that the Soviets soon would be “dropping bombs on us from space like kids dropping rocks onto cars from freeway passes,” as Democratic Senate majority leader Lyndon Johnson put it.

The new agency was created so that the United States would not be caught off guard again in its technological-military competition with the Soviets, and as a means of overcoming the bureaucratic rivalries between the military services that had delayed the development of the American space program. But the central mission of the agency was articulated by Eisenhower’s science advisor James Killian, writing in 1956 that “If there are to be yet unimagined weapons affecting the balance of military power tomorrow, we want to have the men and the means to imagine them first.”

The purview of the new agency changed significantly in its early years, particularly after it transferred most of its responsibilities for the civilian space program to the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which Eisenhower and Congress created later in 1958. But it retained Killian’s charge to imagine the future first, and in so doing became what the Economist magazine called “the agency that shaped the modern world.”

DARPA created (in whole or in part) many of the breakthrough technologies of the past 70 years, which have extended beyond defense into civilian applications. These have included the personal computer, stealth aircraft, the global positioning system (GPS), weather satellites, new types of computer chips, voice-recognition software, drones, and precision-guided munitions. Most famously, in the 1960s the agency fostered the creation of a communications network dubbed the ARPANET, which could survive a partial nuclear attack. Over time it morphed into the modern Internet. More recently, in 2013 DARPA awarded a $25 million grant to a startup biotech firm to research the use of messenger RNA to make vaccines, which led to Moderna’s development of one of the principal mRNA vaccines against Covid-19.

Eisenhower set DARPA in motion, but there are limits to which the organization’s subsequent evolution and successes can be said to reflect his vision. Even so, DARPA reflects his deep understanding, as supreme allied commander in Europe during World War Two, that science and technology had been essential to victory and that Cold War success would require unprecedented collaboration between government, universities, and industry. Walter McDougall, the preeminent historian of the Space Age, observed that Eisenhower was well aware that only the federal government could direct activity on this national scale. This would in turn require him to discard some of “the old verities” about limited government, local initiatives, and rugged individualism: “The United States had to respond in kind to Soviet technocracy.”

DARPA’s creation was consistent with Eisenhower’s appreciation of science and his desire that science become a more prominent part of American life. Another of his 1958 responses to Sputnik was to oversee passage of the National Defense Education Act, which dedicated $1 billion—a vast sum at the time—to reforming science teaching, training science teachers, providing scholarships and graduate fellowships in scientific fields, and promoting the study of foreign languages. Eisenhower worked closely in these matters with Killian and other members of the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC). Killian reported that Eisenhower was “exceptionally responsive to innovative ideas” and the president felt that the PSAC was “one of the few groups that I encountered in Washington who seemed to be there to help the country and not help themselves.”

Although Eisenhower’s “kitchen cabinet” was made up of wealthy businessmen, some of those businessmen worked closely with scientists and their experiences may have been helpful in informing his understanding of what a scientific agency like DARPA needed to be successful. His close friend Amory Houghton, for example, was CEO of what then was called the Corning Glass Works (now Corning Inc.), which relied on the work of sometimes-temperamental geniuses who were as much artists as scientists.

Set up in a mere three months in 1958, much of the secret of DARPA’s success lies in the unusual structure it has had since its inception. Unlike other Department of Defense organizations, DARPA does not have its own laboratories or research facilities. All its projects are contracted out to universities, businesses, and other outside entities. It maintains a minimal bureaucracy and hires eminent scientists as project managers on short-term contracts, typically three to five years. From the beginning, these scientists have been given unusual freedom and encouraged to think big, more like venture capitalists than bureaucrats, and to pursue projects that are too ambitious for private industry.

The program managers operate without the red tape of most funding systems, without political interference, and without the usual mechanisms of peer review or progress metrics. The initial $1 million contract the agency gave to support what became the ARPANET was awarded entirely on the basis of a 15-minute conversation. Many of DARPA’s experiments end in failure, but the agency considers the freedom to fail as a necessary price for achieving revolutionary breakthroughs. DARPA has made immeasurable contributions to American greatness at a relatively modest cost—its 2020 budget was $3.6 billion—and with minimal bureaucracy. It is a prime example of the kind of active, flexible, and successful government for which Eisenhower advocated. And yet many conservatives have been as reflexively opposed to DARPA as they have been, historically, to Eisenhower’s vision of restrained but effective government.

Michael Lewis’s 2018 bestseller The Fifth Risk describes a meeting at which Arun Majmudar, the head of ARPA-E, a Department of Energy agency modeled after DARPA that pursues advanced energy technologies, had lunch with conservative staffers at the Heritage Foundation whose proposed federal government budget eliminated funding for his organization. He told Lewis that the staffers were gracious, “but they didn’t know anything. They were ideologues. Their point was that the market should take care of everything,” a position they maintained even after he gave them numerous examples of breakthrough technologies that failed to find free-market support during their infancy. Fortunately for Majmudar, a Heritage funder was also present who asked if ARPA-E was related to DARPA. When told that it was, she related that her son had fought in Iraq and that his life was saved by a Kevlar vest, a product of DARPA research.

Funding for ARPA-E was restored in the next Heritage budget. But the Trump administration’s first budget eliminated ARPA-E while gutting much of government’s research and development capacities. President Donald Trump in many ways moved the conservative movement away from the market-fundamentalist libertarianism that had long defined it, but his populism fails to recognize the value of experts, science, and competent government. Eisenhower demonstrated how these could be harnessed towards conservative goals.

The modern conservative movement was founded upon a conceptual error. As National Review publisher William Rusher reminisced to the magazine’s editor-in-chief William F. Buckley Jr., “modern American conservatism largely organized itself during, and in explicit opposition to, the Eisenhower administration.” But Eisenhower was in fact an exemplar of effective conservative governance. The modern-day conservative movement should make peace with Eisenhower and revive the Republican tradition he embodied so successfully during his presidency.

This article is part of the American System series edited by David A. Cowan and supported by the Common Good Economics Grant Program. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Geoff Kabaservice is Director of Political Studies at the Niskanen Center and the author of Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, from Eisenhower to the Tea Party. He has written for numerous national publications including the New York Times, Washington Post, and Politico. He also holds a B.A. in Political Science from Yale University, an M.Phil. in International Relations from Cambridge University, and a Ph.D. in History from Yale University.