Henry Clay's Defense of the Strong State

“We are all—people, States, Union, banks—bound up and interwoven together, united in fortune and destiny, and all, all entitled to the protecting care of a paternal government.”

by David A. Cowan

This article first appeared on The American Conservative, July 28, 2022

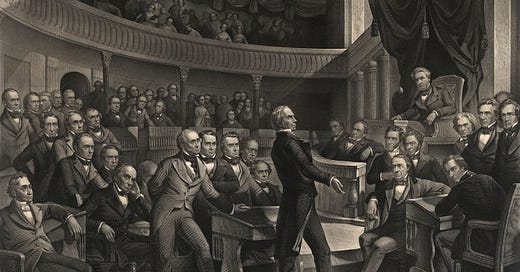

The American System was the vital blueprint for the nation’s transformation into a global industrial power. Alexander Hamilton laid the foundations and Abraham Lincoln would begin its full-scale implementation, but it was Henry Clay who made Hamiltonian economics compatible with Jeffersonian politics. Clay did not just champion specific policies. He wanted to build a strong and resilient state that would unite the nation and abide by republican principles. As this essay series starts to examine the history of industrial policy in America, it is right to begin with one of its most significant visionaries.

Clay was not a Hamiltonian, but in fact a staunch Jeffersonian and product of the South, born in Virginia and building a career in his adopted state of Kentucky. Much like the rest of the Whig party that sprung into being in 1833, Clay entered politics as a member of Thomas Jefferson’s Republican Party. Former Federalists like Daniel Webster joined the Whig coalition, but it was the nationalist wing of the Republican Party, previously led by James Madison and James Monroe, that formed the backbone of the Whigs. Clay believed in a strong state under the Constitution without sharing the Federalist tendency to emphasize authority and hierarchy over equality and freedom.

The Jeffersonian commitment to equality shaped Clay’s desire to build a sophisticated and nationalized economy that would create opportunities for all Americans. In many ways, Clay was drawing inspiration from his experiences in Kentucky, where he saw firsthand a diverse economy in which farmers, merchants, and manufacturers all had a crucial role to play in generating prosperity. The protective tariff, international improvements, and central bank would increase both industrial and agricultural production, establishing a symbiotic relationship between them. By putting forward a comprehensive plan for economic development, Clay hoped to forge a stronger national spirit that could integrate different interests and classes into a more powerful and united America.

The War of 1812, the “second war of independence” as some saw it at the time, was the defining experience for republican nationalists like Clay. Following his message to Congress at the conclusion of the conflict, Madison signed legislation for the nation’s first ever protective tariff and the creation of the Second Bank of the United States in 1816. This aggravated the divide within the Republican Party over the relationship between government power, private virtue, and the common good. The ‘Old Republicans’ abided by the more radical reading of Jefferson’s ideas around limited government and strict constructionism, preparing the ground for the future fracturing of the party.

Republican nationalists continued to prosper under Monroe, making the case for the protective tariff as a means of creating jobs and supporting domestic industries. This would culminate in the 1824 tariff law which increased tariff rates from 20 percent to 35 percent and sparked intense debate between Northern and Southern interests. Speaking in defense of the legislation, Clay coined the term “American System.” He argued that the short-term impact of the tariff increase would be compensated by the long-term gain for the nation as a whole. Division only deepened following the election of John Quincy Adams after the 1824 election was decided in the House of Representatives. Adams supported elements of Clay’s American System but his reelection campaign in 1828 was upended by Andrew Jackson’s accusation that the previous election had been rigged by a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Clay.

The boom years of the Jackson presidency made it easier for the new Democratic Party to dismiss the need for an interventionist state and block the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States. Anti-Jacksonian sentiment became the glue binding the Whig coalition together. The 1830 Maysville Road veto, whereby Jackson blocked federal funding for the Maysville Road, crystallized perceptions of how the Democrats had hindered stable investment in internal improvements. When the Panic of 1837 struck, triggering a long-lasting depression, the debate was transformed as Clay gained the vindication he needed, consolidating the Whigs’ identity around a positive policy platform and convincing voters that the Democrats had failed to stabilize the American economy.

Despite the intransigence of Jacksonian Democrats, state and federal investment poured into railroads across the nation during the 1840s. This has led to the period between 1843 and 1860 being seen as a time of rapid and extraordinary change for the American economy. Railroads accelerated the industrial revolution, supporting mining and opening new markets in lumber, coal, iron, and steel. Railroad corporations became the biggest companies since the demise of the Second Bank of the United States. Even the growth of the railroads, however, could not unite a fractured nation as they spread from east to west instead of north to south.

This era of urbanization, industrialization, and expansion of transportation, succeeded in stimulating domestic demand for manufactured goods. In response, mass production came into being with the growth of factories and the decline of artisan workshops. New technological innovations like the sewing machine appeared. By 1840, the population of the America matched Britain at 17 million people. The gross national product had a long-term growth rate of 3.9 percent, which was higher than Britain’s growth rate of 2.2 percent despite the latter being the larger economy.

It is these vast economic changes that Clay hoped to harness for the common good. Historian Michael F. Holt summarized the American System as including “high protective tariffs to nourish American manufacturing and create a home market for American agricultural products, a national bank to provide a sound and uniform currency, and federal subsidization of internal improvement projects to ease the movement of goods. In later years, when federally funded internal improvements became infeasible, Clay instead promoted distribution of federal land revenues to the states for their own improvements.” The plan devised by Clay was tailored for the specific situation he faced, but it was also based on principles that can still be applied today.

Reasserting economic independence from Britain was central to Clay’s emphasis on the American nature of his program. In part this was to contrast with the British system of free trade, which encouraged other nations to open their markets to world trade even while Britain maintained protectionist measures such as the corn laws and the navigation acts. More importantly, the American System was about resisting British economic dominance. Monroe had already outlined his famous 1823 doctrine against further European interference in the Western hemisphere. Clay believed it was vital for America to prevent its economy from becoming dependent on the import of British manufactured goods, which would place limits on the nation’s freedom.

As well as standing up to the British, Clay was determined to defy Jackson, famously satirized as ‘King Andrew the First,’ and condemn the overreach of presidential authority. The choice of the name ‘Whig’ was intended to pay homage to the Anglo-American heritage of opposing executive abuse from the signing of the Magna Carta to the Revolutionary War. Clay took inspiration not from the Federalists but from Republicans such as Albert Gallatin, who served as Treasury Secretary under Jefferson and Madison but maintained Hamilton’s innovations. Many Whigs shared Clay’s commitment to a strong state, but they believed that this could only be reconciled with republican principles through the leadership of Congress. Years of political combat with Jackson and his successors had not just been about economics. It was a clash of views over the balance of power between the executive and the legislature.

The Maysville Road veto and the Bank War became powerful moments precisely for this reason. Democratically elected legislatures had approved the Maysville Road bill and rechartering the bank, but Jackson used his veto power to block them. Previously, the veto power had been used sparingly as a method of blocking legislation that was believed to violate or undermine the Constitution, not because it was contrary to the president’s political agenda. For Clay, it was crucial that Congress should push ahead with the economic reforms he believed the republic needed. Whigs in the state legislatures also had a role to play. Lincoln was a notable example when he entered politics as a state legislator backing state-funded internal improvements in 1836, his very own “Illinois System”, and defended the state bank.

There was also a different conception of class. Democrats spoke of defending the working classes and protecting their interests against the elites. Whigs rejected the rhetoric of class conflict and believed that classes could be linked together in a system of mutual benefit. Clay declared, “We are all—people, States, Union, banks—bound up and interwoven together, united in fortune and destiny, and all, all entitled to the protecting care of a paternal government.” The American System was truly national in character, designed to integrate the various components of American society. This approach would be perpetuated by Clay’s intellectual descendants in the Republican Party from Lincoln to Eisenhower.

Clay’s policies were clearly a product of a particular time and place. The economic needs of a nascent great power are different from those of the global superpower that exists today. This does not mean the principles behind Clay’s program are no longer applicable. The American System was designed to bring about a strong state that could secure economic independence and harmonize different classes and interests under the leadership of Congress. A strong state could achieve these goals through policies that are specifically targeted and designed to support the growth and development of the American economy.

For America today, a strong state still requires an active Congress. Senators and Representatives should take up the initiative, just as Clay did, to identify policy solutions that can enhance American industrial power. The CHIPS Act, despite its defects, is an important example of how legislators are currently acting to address America’s economic vulnerabilities. But greater ambition is required. American industrial policy cannot be sustained by executive orders alone. It requires the full power of Congress to become a reality, allowing America to become more economically resilient and opening opportunities for citizens across the republic.

This article is part of the American System series edited by David A. Cowan and supported by the Common Good Economics Grant Program. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors.